AARON JAY KERNIS Musica Celestis

performed by Ariel String Quartet

MOZART Piano Concerto No. 23 in A major

performed by Orchestre de Paris

TCHAIKOVSKY Serenade for Strings in C major

performed by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

My least favorite subject in grade school was English. The books we had to read were really boring and I hated writing. Like, really hated it. It always felt to me like I had to state something obvious, like “Macbeth killed Duncan and felt bad about it”, but turn it into a two page, double-spaced essay, just… because. I couldn’t appreciate the challenge of structuring a solid argument, and didn’t see the creative aspect of building a logical flow from sentence to sentence.

Writing music, on the other hand, I always appreciated. Not that I’m any good at it; actually, I think my simultaneous love for music and inability to write it is what helped me see the ingenuity required to craft a beautiful piece of music. That ingenuity is what you often hear people to Mozart’s music, but I would only be the ten-millionth person to give Mozart that credit. I’ll go one step further and try to explain why he deserves it.

The way Mozart crafts a musical idea is so well-structured to the point that the flow from one melody to another almost sounds obvious, like there couldn’t be any other direction for a melody to go other than the one he chose. But in composition, that of course is not the case: there are infinite options when it comes to deciding which notes come next. I’ve designed a little exercise to help us think like a composer and face the same decisions he or she would make when constructing a musical phrase. Below are three paragraphs which all use the same sentences but are ordered differently. Read them and notice the difference that sentence order makes.

It was when we used to live in Richmond. All of us had been a part of something bigger than we could have imagined. It was important work, work that needed to be done. That our work was used to accomplish terrible deeds was something we could never have foreseen. Now we live with the consequences, forever burdened by the weight of our past lives.

It was important work, work that needed to be done. All of us had been a part of something bigger than we could have imagined. Now we live with the consequences, forever burdened by the weight of our past lives. That our work was used to accomplish terrible deeds was something we could never have foreseen. It was when we used to live in Richmond.

That our work was used to accomplish terrible deeds was something we could never have foreseen. It was when we used to live in Richmond. All of us had been a part of something bigger than we could have imagined. Now we live with the consequences, forever burdened by the weight of our past lives. It was important work, work that needed to be done.

These all read pretty differently, right? What I love about this exercise is how it demonstrates the importance of sentence flow. You might better understand what I mean if you look at the last sentence of each paragraph. The final sentence feels different in each because of how you arrived at it. For example, ending with “forever burdened by the weight of our past lives” implies that the character feels regret because of their actions, whereas ending with “it was important work, work that needed to be done” implies that the character feels that they ultimately have to move on.

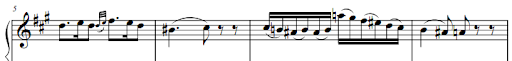

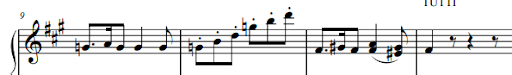

I don’t mean to suggest that one of these paragraphs is “correct” and the others “incorrect”. Instead, I want to show that there’s a lot of decision making that takes place when a composer attempts to create music that flows logically and fluidly from beginning to end. Let’s look at (and listen to!) some music now. Below is the opening of the second movement of the piano concerto, separated into three lines of music. I hope that now you’ll be able to see and hear how Mozart takes a handful of ideas and weaves them into one, sorrowful whole. Follow along with the following music while listening to the start of the second movement. Don’t worry if you are unable to read the notes themselves. Instead, follow along with the direction and shape that the notes take, like if they are rising or falling.

What did you notice? Did each sentence sound like it logically led to the next? There were no jarring transitions, right? I want to highlight three details that will help explain how Mozart achieved this fluidity in his music.

- The end of each line of music ends with some rests. Rests can often imply the end of an idea, a lot like a period at the end of a sentence.

- Each “sentence” starts with the same rhythm before branching off in different directions. It gives the listener the idea that these sentences are related to each other.

- Notice the number of bars that each “sentence” occupies. It’s four bars for each idea, and if you listen again you might be able to hear that each of these four bars can be heard as pairs of two-bar fragments, a beautiful symmetry.

There are a lot of other, more technical details that go into crafting a musical idea like Mozart did which aren’t worth going into for the purposes of this document. The goal here is to illuminate the decision-making process that goes into composing music. A musical idea like the one we just examined may sound boringly simple on the surface, but is in fact a feat of composition.

Discussion Questions:

- Most visual art, like painting or sculpture, is unique in that it doesn’t unfold over time like music does. Can you think of another creative process which requires you to organize your ideas into a certain order? Perhaps it was a writing assignment, producing a video, or even a dance performance. Share your experience!

- Poetry in particular is an art that relies heavily upon flow from one idea to another, using rhythm and rhyme to help string ideas together. If you haven’t already, watch the poem delivered by Amanda Gorman at the Presidential Inauguration. Hopefully, with this new way of looking at compositions, you’ll be able to hear something new in her poem. Share some details you noticed that contributed to the flow of her poem – be specific.